By: Shannan Herbert

Today, we spotlight Zsudayka Nzinga Terrell, an award-winning artist, educator, advocate, and small business incubator whose work has been featured internationally. As the former Vice President of Black Artists of DC, she is transforming Washington, DC’s Ward 7 through her co-founded space, Terrell Arts DC.

Through partnership with the Anacostia Arts Center powered by Wacif, Zsudayka has been able to showcase her multidisciplinary art and engage with the community. Her participation reflects Wacif’s mission to foster the growth and sustainability of local artists, helping them thrive within the creative economy.

Terrell’s advocacy extends beyond her art, as she actively fights for equitable treatment of artists within the industry. She has earned a curatorial grant from the DC Commission of the Arts and Humanities, curated multiple exhibitions, and teaches art programming for nonprofits, private, and charter schools. Terrell also runs a family business with her husband, selling and exhibiting their art while assisting teachers and homeschool families with arts-integrated education.

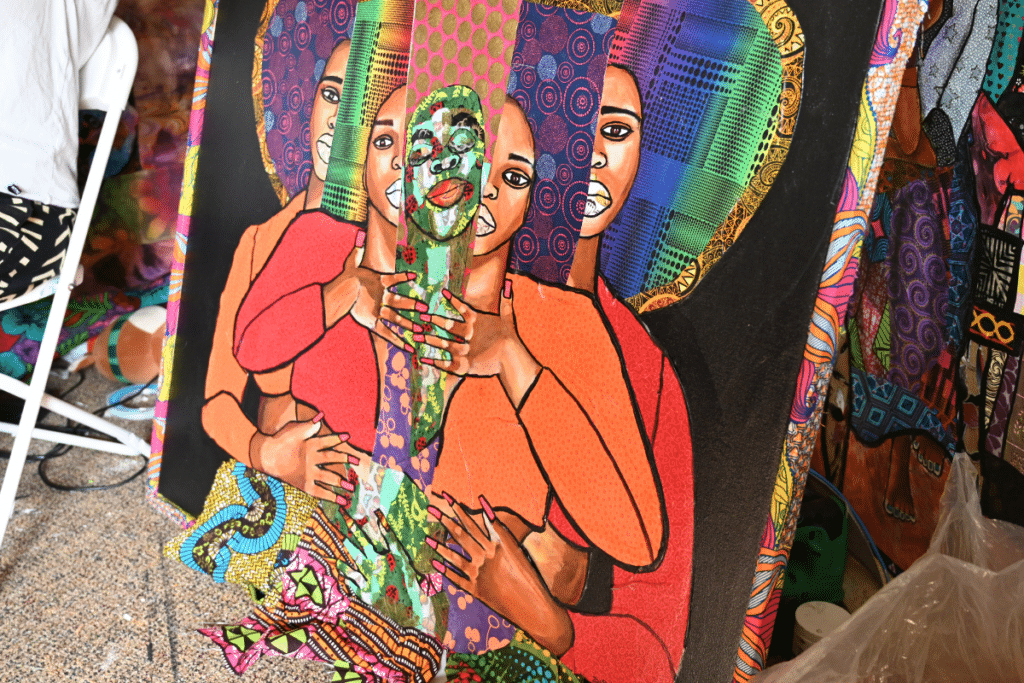

Rooted in cultural anthropology, Terrell’s art documents the Black American experience and challenges societal norms. Her work has been featured in outlets such as Voice of America and The Washington Post. Terrell continues to make a profound impact by creating a community art space in Ward 7. Her passion for fairness, community engagement, and access to art redefines what it means to be an artist, an advocate, and a leader in the creative economy

Shannan Herbert: Thank you for welcoming us into your space. I’ve been following your work for some time but I’m curious about your journey. How did you get your start?

Zsudayka Terrell: It’s hard to believe I’ve spent 20 years in the arts, starting as a spoken word artist in the late ’90s during the Love Jones and Def Poetry Jam era. I performed across cities, opening for concerts like The Roots, while also writing poetry and exploring drawing.

Despite my talent, my parents pushed me toward law, leaving me unsupported in my artistic journey. Feeling that poetry was often underappreciated, I turned to visual art, allowing my work to speak for itself.

In Colorado, I launched a Black Arts Festival and joined the Sankofa Art Collective, where I met quilt artist Dawn Williams- Boyd, who saw potential in me and motivated my growth. In Atlanta, I connected with mentor James Lee Brooks, who taught me color theory, transforming my approach to painting.

When I moved to DC, I read a book about the concept of mastering a skill through 10,000 hours of practice. Inspired by this idea, I decided to dedicate that time to painting and studying art. While teaching myself, I developed lesson plans and began teaching art to kids. Eventually, I committed myself to mastering painting and quit my job to focus full-time on my art, particularly portraits of Black women and themes of empowerment.

By 2016, I felt I had achieved mastery, gaining recognition through group shows and a youth art competition. However, the events of 2020 brought both challenges and unexpected recognition for Black artists. Despite the tragedy of George Floyd’s death, it elevated my profile, landing me on a list of top Black artists to watch, which transformed my career. Now, I sell my art, collaborate with consultants, participate in museum shows, and have representation by Stella Jones Gallery in New Orleans.

Shannan Herbert: That is quite a journey! I love the transition from poetry to visual art and with the context you’ve provided, I can see the poetry in your work.

Zsudayka Terrell: Yes, a lot of it is based on little things I’ve jotted down.

Shannan Herbert: Talking with you feels very direct, yet your work conveys many subtle, indirect messages that I notice and appreciate. It’s like you said earlier, “being present but not wanting to be too visible.”

Zsudayka Terrell: It’s hard. As a woman, it’s a different conversation than it is for men. In male-dominated industries, you try to be as powerful as you can, but people might still approach you with superficial comments, not realizing the impact it has. Poetry, too, is a rough world where many people are lost in their imagination, which can be frustrating.

Shannan Herbert: Is this what inspired you to create a community art space in Ward 7?

Zsudayka Terrell: DC faces a significant shortage of studio space, a persistent issue for me as a taxpayer. It’s frustrating to be directed to studios in Hyattsville or Mount Rainier when I want to work in DC, which complicates grant eligibility. Art requires specific conditions that typical office spaces can’t provide, such as proper ventilation and noise control. After moving to Brookland, I found the area East of the River is severely underserved, with failing schools and limited grocery options.

Despite efforts to engage the community, we’ve faced hurdles. There’s a clear need for art, especially to inspire local youth, who often lack visible role models. Creating a community art space in Ward 7 is essential. We envision a welcoming environment for families, with youth workshops and community engagement. Research shows that galleries can transform communities, as seen with the Anacostia Arts Center.

Shannan Herbert: Right. This is one of the reasons why the Anacostia Arts Center is so special. Our gallery space invites artists to display their work, allowing visitors to engage and connect with them.

Everyone needs a place to start. If this space encourages people to be brave and say, ‘I want to share something I created,’ that takes real courage. Being vulnerable through art is powerful.

Zsudayka Terrell: When I first visited the Arts Center to vend, it was my entryway into the community, where I learned about other vending opportunities. Now, those spaces have helped bring a community to the area, and there are restaurants and activities. There’s also more visibility for Black professionals in the neighborhood, which is crucial.

Shannan Herbert: You also have experience curating exhibitions. How has that influenced or changed your perspective on entrepreneurship in the arts?

Zsudayka Terrell: Most people don’t approach art as a business, and that’s a problem. Curating has shown me this clearly. Many artists lack professional photos, headshots, resumes, press kits, and artist statements. Additionally, many don’t understand the value of LLCs, accountants, or getting their work appraised, which could open doors for business opportunities. This constant scramble to get the basics in place makes the process difficult. For example, galleries have strict rules on framing and safety that artists often aren’t prepared for, and most galleries don’t insure artwork, leaving artists who can’t afford their own insurance vulnerable.

Last year, I ran an 8-week boot camp for Black women artists, helping them develop headshots, resumes, artist statements, and group shows. This type of program needs to happen regularly because having these professional tools changes everything for artists.

Shannan Herbert: It sounds like you view yourself as an artist, advocate, teacher, and mentor to many young artists. I sense a protectiveness in you, ensuring everyone that you work with receives a fair shot and equitable treatment. Whether it’s bringing people to art shows, curating events, or advocating with organizations, you show up for your community.

Zsudayka Terrell: Yes, I’ve been fortunate because my network is mine. I can say things that others can’t, as it would cost them too much.

Shannan Herbert: When considering Wards 7 and 8, how can we ensure that new residents and businesses are informed about their potential impact on the community? What do you see as your role, and that of other artists, in fostering cultural competency in these discussions?

Zsudayka Terrell: That’s why having an art center is crucial. It provides a foothold, a space where people can come together for these important conversations. We recently started a Ward 7 art collective, with a diverse group working on organizing it as a 501(c)(3). While safe Black spaces are essential, inclusivity is also important to me. This collective will serve as a hub, so no one can say, “We didn’t know who to reach out to.” We’ve created a space where they can.

Shannan Herbert: Absolutely, and if you ever want to have any of those meetings at the Anacostia Art Center, feel free to reach out.

Zsudayka Terrell: Yes, I’d love that. I actually want to organize a full tour around the block, highlighting how the Anacostia Arts Center has transformed the area and who engages with the art. Many times, people often those struggling with addiction come to the center and say, “You painted this? It looks like my auntie,” or they’ll take pictures. Even people just passing by, dealing with their own challenges, stop to look, take pictures, or peer through the windows as we move pieces in and out of the gallery.

It’s revolutionary people who’ve felt ignored their entire lives stumble upon art that reflects them, something they never thought they’d see in their neighborhood. Last time, a group asked, “How long has this been here?” and we told them, “It’s been here for a while.” It’s amazing how many people don’t realize what’s in their own community.

Shannan Herbert: In a perfect world, what would funding opportunities for artists look like? What do artists truly need funding for, and what structures would best support them?

Zsudayka Terrell: In a perfect world, I wish for universal living expenses for artists to ensure secure housing, allowing them to thrive. Delayed funding often means awards don’t cover rent in time. I envision consistent, smaller funding opportunities for emergencies, as many artists lack insurance. If I had $2 million, I’d build a communal space for artists to practice, share supplies, and connect with schools, creating an environment where resources are accessible, and no tools go unused.

Shannan Herbert: That was perfect. There are many layered issues you mentioned– insurance, access to emergency funds, and more. It’s not just about providing money; without wrap-around services to address these needs, the funding will never be sufficient.

Zsudayka Terrell: Right, even transporting art can be incredibly expensive. My husband and I even considered buying an Amazon truck to simplify the process. Instead of charging exorbitant fees, we could provide a vehicle for artists who need help moving their work. It’s essential to think about practical solutions that make these resources accessible to the community.

Shannan Herbert: I love that idea. It’s about the business of being an artist while creating opportunities for others.

Zsudayka Terrell: Yes, thinking about ways we can serve artists. Even small efforts can have a big impact.

Shannan Herbert: Indeed. Thank you so much Zsudayka.

Zsudayka Terrell: Thank you.

Meet Shannan Herbert, CEO of Wacif

I am honored to introduce myself as the new Chief Executive Officer of Wacif. As we embark on this journey together, I am filled with a deep sense of purpose and commitment to our mission of inclusive entrepreneurship, community wealth building, and equitable economic development.

As we look ahead, I am dedicated to building upon the strong foundation laid by my predecessors. Wacif has been a source of empowerment in our community, and I will continue that tradition by leading with empathy, integrity, and innovation. We will continue to amplify the voices of small business owners and create pathways to prosperity for all members of our community.

In the coming weeks and months, I look forward to connecting with members of our community and finding creative ways to bring new stories to our readers. Together we will inspire and uplift one another and write the next chapter in our organization’s story.

About The Washington Area Community Investment Fund Established in 1987, the Washington Area Community Investment Fund’s mission is to increase equity and economic opportunity in underserved communities in the Washington, DC area by investing knowledge, social, and financial capital in low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs. Our mission is driven by three strategic pillars: inclusive entrepreneurship, community wealth building, and equitable economic development, and is fulfilled by providing access to capital products and services, and capacity building technical assistance to low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs. Wacif has been continuously certified as a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) since 1996, making the organization one of the nation’s first CDFIs.